Manifest New Emotions Through Show Dont Tell Writing

As writers, we often chase the elusive spark that transforms words on a page into vibrant, lived experiences for our readers. We want them to feel what our characters feel, see what they see, and understand the world we've built from the inside out. This isn't just about conveying information; it's about crafting an immersive journey, and at the heart of this craft lies the indispensable principle: Show, Don't Tell: Manifesting New Emotions in Writing.

Forget dry descriptions and overt statements. "Show, Don't Tell" is your secret weapon, inviting readers to step into your narrative and experience emotions firsthand, rather than merely being informed about them. It's the difference between a character being sad and a reader feeling their sorrow as a heavy blanket. This isn't just a technical rule; it's a philosophy that empowers you to paint with vivid imagery, dynamic verbs, rich details, and compelling actions, creating a mental canvas that comes alive in the reader's mind.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways for Showing, Not Telling

- Go Beyond Reporting: Instead of stating emotions or facts, demonstrate them through sensory details, actions, and dialogue.

- Empower Your Reader: Showing invites readers to interpret and engage deeply, forging a personal connection to your story.

- Use the "Camera Test": If a camera can't capture it, add more specific, visual details.

- Leverage Action & Dialogue: Character actions reveal traits, and their words expose their inner world.

- Strategic Telling: Know when to summarize less important details to maintain pacing and avoid reader fatigue.

- Cultivate Curiosity, Skill, & Confidence: These three pillars are crucial for mastering the balance between showing and telling.

- Practice Makes Perfect: Engage in targeted exercises to sharpen your ability to evoke emotion and create immersive scenes.

The Heart of "Show, Don't Tell": Why It Matters for Emotion

Imagine watching a movie where a narrator simply states, "The hero was brave," or "The villain was cruel." You wouldn't feel much, would you? Now picture the hero fearlessly facing down a monstrous beast, shield raised, a determined glint in their eye, despite trembling hands. Or the villain calmly stroking a cat while ordering destruction, a faint, chilling smile playing on their lips. The impact is entirely different.

This is the power of "Show, Don't Tell." In writing, telling removes nuance, stripping away the layers that make a story rich and relatable. It restricts your reader's imagination, hand-feeding them conclusions rather than inviting them to discover. When you tell, you give information. When you show, you provide an experience. You give your reader the task of witnessing, interpreting, and connecting with the text on a deeply personal, often emotional, level.

Think about the human experience itself. We don't just feel emotions; we manifest them through our bodies, our words, and our actions. Our cheeks flush with embarrassment, our voices crack with grief, our fists clench in anger. "Show, Don't Tell" is about translating these human manifestations onto the page, allowing the reader to infer, empathize, and form their own opinions, making the story uniquely theirs.

When Information Isn't Enough: The Reader's Experience

The goal of creative writing isn't just to transfer data; it's to share a human experience. When you simply tell that Mary was embarrassed, you're giving a summary, an analytical conclusion. The reader passively receives this information. But when you show Mary seeing a bright red 'F' on her paper, her cheeks burning, her fingers crumpling the test into a ball as she shoves it into her desk, hoping no one notices – you've transported the reader into that moment.

Suddenly, the reader isn't just told about embarrassment; they feel the heat in Mary's cheeks, the tension in her fingers, the desperate wish for invisibility. This kind of showing empowers the reader, granting them agency within your narrative. They become an active participant, piecing together clues, forming their own interpretations, and ultimately, building a much deeper, more specific, and profound relationship with your text. It moves beyond mere understanding or agreement; it fosters genuine engagement.

Seeing is Believing: Dissecting Show vs. Tell

Let's break down how this principle operates across different facets of your writing, from character emotions to world-building.

Emotions in Action

Tell: "Mary was embarrassed."

This gives us a label, but no feeling.

Show: "Mary saw the large, red 'F' on her paper, her cheeks flaming. She crumpled the test and shoved it into her desk, hoping no one noticed."

Here, embarrassment is revealed through physical reaction (flaming cheeks), action (crumpling, shoving), and internal thought (hoping no one noticed). We don't need the word "embarrassed" to understand how Mary feels.

World-Building Beyond Description

Tell: "Mordor was a scary place."

Vague, unconvincing. Why was it scary?

Show: J.R.R. Tolkien, describing a desolate landscape: "...choking pools of ash and mud crawled, pale white and grey..."

Tolkien doesn't say "scary." Instead, he uses evocative sensory details ("choking pools," "ash and mud crawled," "pale white and grey") to create an oppressive, lifeless atmosphere that inherently feels terrifying. The landscape itself embodies the fear.

Internal States Made External

Tell: "I found the trail challenging."

This is a direct statement, an opinion, but it lacks the visceral struggle.

Show: Cheryl Strayed, describing a grueling hike: "Within forty minutes, the voice in my head was screaming... gasping and groaning in pain and trying to remain stooped in an upright position... willing myself forward when I felt like a building with legs."

Strayed transforms the abstract idea of "challenging" into a brutal, physical, and mental battle. We hear the screaming voice, feel the gasping pain, and witness the sheer willpower required to keep moving. The reader is right there, pushing forward with her.

These examples highlight a crucial point: showing isn't just about adding more words; it's about choosing the right words – specific, sensory, action-oriented – that create an image or sensation in the reader's mind, allowing them to experience the narrative.

Beyond Theory: Actionable Strategies to "Show"

Now that we understand the 'why,' let's dive into the 'how.' These strategies will equip you to manifest new emotions and richer experiences in your writing.

The Camera Test: Visualize Every Detail

This is perhaps the most fundamental technique. Imagine a camera filming your scene.

Ask yourself: "Can a camera actually see what I'm describing?"

If you write, "The kingdom lived in harmony," a camera wouldn't capture "harmony." What would it see? Perhaps "A kingdom nestled by the sea, where cobblestone streets bustled with laughing children and merchants exchanged goods with gentle smiles." The specific details—sea, cobblestone, laughing children, gentle smiles—are what a camera could record, and they show harmony.

This test forces you to move from abstract concepts to concrete, sensory details. What does your character smell, hear, touch, taste, see? What are their subtle facial expressions, their posture, their fidgets? These specifics are the raw material for showing.

Dialogue as a Window to the Soul

Characters' words are natural reflections of their feelings, beliefs, and personalities. They add color, tension, and revelation far beyond a simple descriptive tag.

Tell: "He was angry."

Show: "'I can't believe you did that!' he snarled, his voice tight, hands balled into fists at his sides."

The dialogue "I can't believe you did that!" coupled with the active verbs "snarled" and the physical description "hands balled into fists" vividly shows his anger. The emotion isn't stated; it's enacted.

Authentic dialogue, complete with pauses, interruptions, and non-verbal cues (like sighs or averted gazes), can reveal layers of emotion and subtext that flat exposition never could.

Actions Speak Louder Than Words

A character's nature, their moral compass, their hidden fears, or their deepest desires are best revealed not through your direct statements about them, but through their deeds and behaviors.

Tell: "She was a liar."

Show: "When questioned about the missing cookies, she met his gaze for a second too long, then quickly glanced at the floor, a faint tremor in her lower lip as she swore she hadn't seen them."

The slight hesitation, the averted gaze, the trembling lip—these actions are subtle, but together they paint a picture of deceit. The reader concludes she's lying without being told directly.

Whether it's a small gesture, a significant choice, or a repeated habit, actions are the bedrock of characterization through showing.

The Revision Power-Up: Tell First, Show Later

Don't feel pressured to get it perfect in your first draft. Often, a good strategy is to "tell" in your initial draft to simply get the story down and outline your ideas. This is your skeleton.

For instance, you might write: "Sarah was nervous about her interview."

During rewriting, revisit these "told" sections. This is where you bring out your "Camera Test" and flesh out the scene with showing.

Revision: "As Sarah waited outside the office, her palms grew slick, and she caught herself smoothing her skirt for the fifth time. The insistent tap of her foot against the tiled floor echoed the frantic beat of her heart."

Here, "nervous" is replaced by physical sensations (slick palms, smoothing skirt) and actions (tapping foot), allowing the reader to experience Sarah's anxiety.

This iterative approach allows you to draft freely, then consciously refine and enhance your writing with evocative showing techniques.

Breaking the Rules: When "Telling" Serves Your Story

"Show, Don't Tell" is powerful advice, but it's not an unbending commandment. There are strategic moments where "telling" is not only appropriate but necessary for efficient and effective storytelling.

Bridges, Not Destinations: Summarizing Unimportant Periods

You don't need to show every single moment of a character's life. If your character travels from Point A to Point B, and the journey itself isn't critical to the plot or character development, tell it.

"He traveled for three days across the dusty plains before reaching the city."

This succinctly moves the plot forward without bogging down the reader with unnecessary details of a uneventful journey.

Trying to show every mundane detail would exhaust the reader and dilute the impact of truly important scenes.

The Unsung Characters: Describing Minor Players

For characters who appear briefly and aren't central to the story, a quick "tell" can be more efficient than elaborate showing.

"The shopkeeper, a stern woman with sharp eyes, quickly tallied his purchase."

We get enough information to visualize her without investing heavily in her backstory or internal thoughts.

Unless a minor character plays a surprisingly pivotal role, a simple descriptive "tell" can suffice.

Necessary Information, Delivered Swiftly

Sometimes, you just need to convey facts or context quickly to set the stage or explain a complex situation. This is where declarative telling shines.

"The war had lasted for ten years, devastating the northern provinces and depleting the nation's resources."

This provides crucial background information efficiently, allowing you to move into the story's present action.

This type of telling is often found in opening paragraphs, historical overviews, or technical explanations.

Strategic Contrast and Pacing

Intentionally "telling" can create a powerful contrast with more evocative, "showing" passages. A moment of declarative clarity can highlight the emotional intensity of a subsequent shown scene. It also helps manage pacing, slowing down for important emotional beats and speeding up for transitions or less crucial information.

A healthy balance prevents reader fatigue. Constant, detailed visualization can be mentally taxing. Prioritize "showing" for the most significant, rich, and vibrant parts of your story – the moments of emotional climax, profound character shifts, or critical plot points. Use "telling" for the less critical information, the transitions, and the background noise.

The Art of Balance: Weaving Show and Tell Together

Mastering "Show, Don't Tell" isn't about eliminating all telling; it's about finding the perfect equilibrium. This balance is supported by three crucial elements: Curiosity, Skill, and Confidence.

Pillar 1: Cultivating Curiosity

Curiosity is an exploratory, empathetic mindset that helps you discover endless entry points for deeper exploration and guides you on which details to focus. It's about looking beyond the surface.

Exercises for a Curious Mind:

- Five-Minute Freewriting: Set a timer for five minutes and write continuously, letting your stream of consciousness flow. Don't edit, just write. This helps access direct experience and sensory input without judgment.

- Character via Senses: Describe a character using only their sensory details—what they smell like, the sound of their voice, the texture of their clothing, the way light hits their eyes (e.g., "Her eyes were ancient forests" instead of "Her eyes were green"). Avoid directly naming senses. Use specific details, similes, or metaphors.

- Unique Intense Experience: Choose a powerful personal memory (joy, fear, awe) and describe it using only sensory details and direct perception, without naming the emotion. How did your body react? What did you hear, see, feel?

- New Environment Deep Dive: Imagine an entirely new setting—a medieval village, a robotic factory on Mars, a city under the sea. Describe it in vivid sensory, emotional, and even mental detail. What are the dominant colors, sounds, smells? What's the mood of the inhabitants?

- Rewrite from Multiple POVs: Take a short scene and rewrite it from at least three different perspectives. Consider a different gender, someone who is colorblind, an older person, a caffeine addict, a best friend, an omniscient narrator, an animal, or a sworn enemy. Notice how the POV organically changes what gets shown and what is perceived.

- Read Like a Writer: When you read, don't just consume. Actively deconstruct. How does the author create immersive perspectives? What specific details do they use to evoke emotion? Seek out unfamiliar books and authors, then try to emulate that curious deconstruction in your own work.

Pillar 2: Sharpening Your Skill Set

Curiosity identifies the "what" to show; skill provides the "how." This pillar involves harnessing the foundational tools of good creative writing and literary devices to convey mood, patterns, associations, and deeper meanings.

Exercises for Craft Mastery:

- Employ Metaphor and Simile: Use these devices to show similarities between two unlike things, adding depth and imagery. For example, instead of "The emergency blanket was wrinkled," write, "The emergency blanket crinkled like a bag of chips." Or, "joy was a lemon-yellow dress."

- Write Without Adjectives or Adverbs: Challenge yourself to write a poem or short story using only nouns, verbs, and other literary devices. Instead of "He was tall," write "He towered over us." This forces you to use stronger verbs and more precise nouns to convey imagery and action.

- Convey Emotion Through Mood: Write a short story or poem where a specific feeling (e.g., anticipation, guilt) is palpable as a mood throughout the piece, without ever directly naming that feeling. Use setting, dialogue, and character actions to build the atmosphere.

- Study New Literary Devices: Beyond metaphor and simile, delve into personification, imagery, symbolism, alliteration, anaphora, irony, juxtaposition, and more. Understand how they work and practice integrating them into your writing.

- Transcribe Podcast Dialogue: Listen to a podcast and transcribe a segment of dialogue. Then, add descriptive body language, scene details, and internal thoughts around the dialogue to advance the story and build mood. What are the unspoken cues? What's happening in the background?

- Emulate Master Authors: Choose a writer whose style you admire (e.g., the conciseness of Hemingway, the long, descriptive sentences of the Brontë Sisters). Select a short passage from their work and try to rewrite your own passage in their distinctive style. This isn't plagiarism; it's an exercise in understanding craft.

- Challenge Yourself with Specific Forms: Work within the constraints of a specific poetic form (like a sonnet or haiku) or a prose form (like flash fiction or a specific genre's conventions). These boundaries often push you to be more creative and precise with your existing skill set.

Pillar 3: Embracing Confidence

The final, and perhaps most challenging, pillar is confidence. It’s about trusting your reader and, crucially, trusting yourself.

Trusting Your Readers

A common fear is that if you don't explicitly tell your reader everything, they won't "get it." This leads to over-explaining and removes the very magic of showing. Trust that your readers are intelligent, imaginative, and capable of interpreting your work richly and meaningfully, even if their interpretation isn't exactly what you intended. Removing ambiguity by always "telling" often strips away the artistry of storytelling. When you provide clues and allow them to connect the dots, you respect their intelligence and deepen their engagement. It allows for a more profound emotional connection, as readers feel they've discovered the emotion rather than being presented with it. This is where you might find readers truly delving into how different facets of our inner worlds can surface.

Defining Your Intent: Creative vs. Didactic

Be clear about your writing's purpose. Are you writing didactically, aiming primarily to inform directly (like this article, which often "tells" to convey information efficiently)? Or are you engaged in creative writing, aiming to create a shared human experience through immersive entry points? Creative writing prioritizes showing to deeply engage the reader. Consider Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace: his didactic philosophical digressions are often skimmed or forgotten, but the vivid "showing" of his characters' struggles and triumphs remains timeless and deeply impactful.

Believing in Your Unique Voice

Your world, your perspective, your unique way of seeing things – these are valuable. Many writers hold back, "telling" for safety rather than diving into the intimate act of "showing" because they lack confidence in the inherent worth of their own creative vision. Believe that the unique world you hold within you, the emotions you want to convey, are deserving of being experienced by others. Embrace the permission to create intimately; it’s the only way readers can truly experience your world.

Welcoming Reader Engagement

Remember that readers want to read. They come to your work with an open mind, eager to explore new experiences and emotions. Writing, when done with intention and care, is a win-win situation, offering value to both the author and the reader. Not every reader will connect with every piece of writing, and that’s okay. The goal is to offer a genuine, immersive experience, trusting that those who resonate will find profound meaning.

Your Next Chapter: Practicing the Art of Emotional Storytelling

Mastering "Show, Don't Tell" is an ongoing journey, not a destination. It's a continuous practice of sharpening your observational skills, expanding your literary toolkit, and cultivating a profound confidence in your voice and your reader's ability to connect.

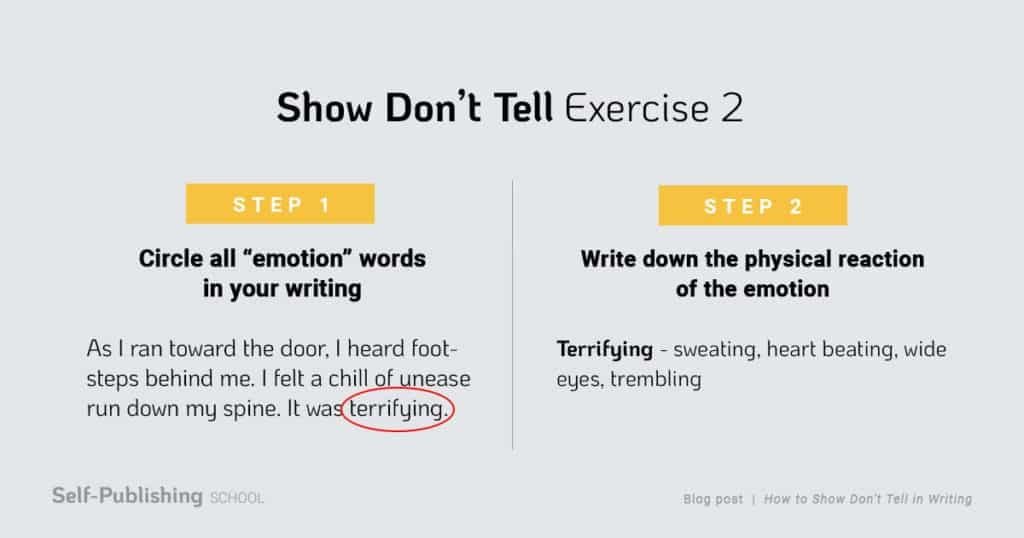

Start small. Pick a scene you've already written and highlight every instance where you've "told" an emotion, a description, or a character trait. Then, challenge yourself to rewrite those sections, applying the Camera Test, leveraging dialogue, focusing on action, and embracing the exercises for curiosity and skill.

The goal isn't perfection overnight, but consistent effort. With each conscious choice to show rather than tell, you'll find your writing becoming more vibrant, your characters more alive, and the emotions you manifest resonating more deeply with every person who turns your pages. Go forth and make your readers feel.